Helping Students Master their Mindset through Metacognition

Imagine the following: You teach anatomy and your learners are rapidly approaching their first exam. One of your learners waits until the last few days before the exam to start studying. Once she starts, she only spends an hour or two each day reviewing, and primarily reviews from the PowerPoint slides rather than going into the laboratory. When she visits the laboratory, she brings a list of structures to identify and checks them off one by one as she studies a dissection prepared by teaching assistants. On the day of the exam, she receives a poor exam grade because she was unable to remember the names of specific structures, or their relationship to one another. When she receives her grade, she is surprised because she used the same strategies that have always worked for her in other courses. What went wrong?

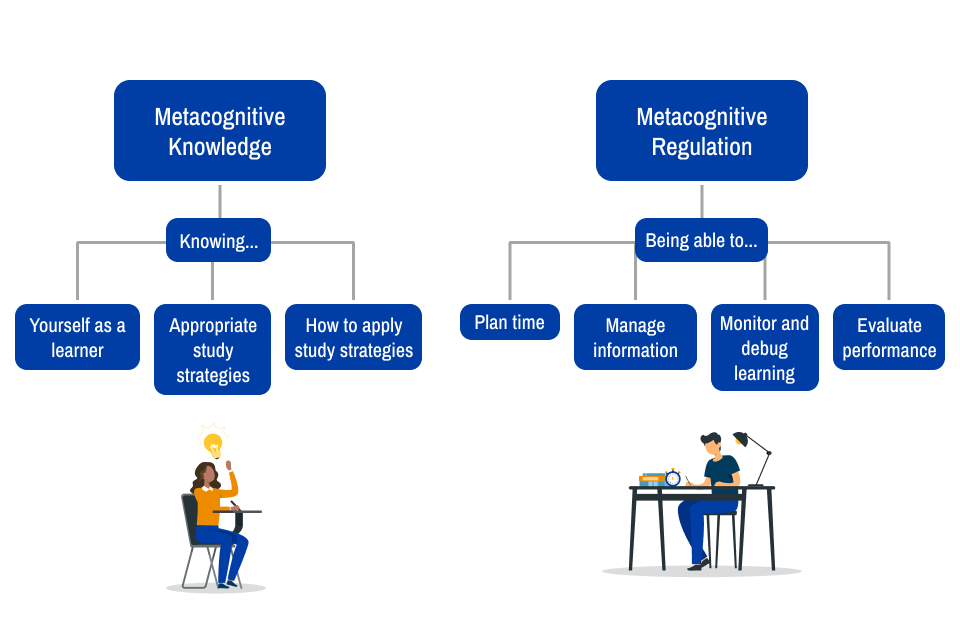

It is likely that our learner struggles with metacognition, or “thinking about thinking.” More specifically, metacognition is the knowledge of how learning occurs, and the ability to orient, plan, monitor and adjust one’s own learning. Metacognition plays a crucial role in how we learn, solve problems, and make decisions and requires awareness of one’s own cognitive processes and the ability to regulate them. Ultimately, that awareness and ability to regulate cognitive processes is associated with increased academic performance and increased ownership of one’s learning. Metacognition, broadly, can be broken down into two main components:

- Metacognitive knowledge: Understanding what you know and how you come to know it. Metacognitive knowledge includes knowing about yourself as a learner as well as knowing about different study strategies and when to use them.

- Metacognitive regulation: The ability to plan, monitor, and evaluate cognitive processes. This includes organization of your time and materials, such as allocating sufficient time to preview and review course content. It can also include making charts and tables, including self-assessments in your study plan to make sure you are learning material. Finally, it can include evaluating your own performance to determine if your learning goals have been achieved or not, and knowing how to adjust your strategies as needed.

Our learner above did not make an anatomy study plan that started far enough in advance

to learn the amount of material. Once studying, she failed to choose an appropriate

method for studying for an anatomy practical exam, instead relying on methods that

may be better suited for other learning tasks. She did not appropriately monitor whether

she accomplished her study goals by quizzing herself on different structures in different

contexts. Instead, she gave herself a false sense of confidence by studying from a

checklist with an expertly prepared dissection. Once she finished the exam, she did

not accurately evaluate her performance.

Our learner above did not make an anatomy study plan that started far enough in advance

to learn the amount of material. Once studying, she failed to choose an appropriate

method for studying for an anatomy practical exam, instead relying on methods that

may be better suited for other learning tasks. She did not appropriately monitor whether

she accomplished her study goals by quizzing herself on different structures in different

contexts. Instead, she gave herself a false sense of confidence by studying from a

checklist with an expertly prepared dissection. Once she finished the exam, she did

not accurately evaluate her performance.

Mastery of both metacognitive knowledge and regulation is crucial to develop into a lifelong, self-directed learner who is prepared for professional practice in an ever-evolving landscape. So, how might we develop these skills in our learners? Below are some evidence-based strategies:

- Encourage reflective practice: Journaling, exam wrappers and other opportunities for reflection allow students to take ownership of their learning experiences and adopt a growth mindset. Reflection can be as simple as asking a learner to identify what worked well, what did not work well, and what they would change before next time. Reflection can also be more situated in course material by, for example, asking students to describe a patient problem and reflect on their own skills and perceptions related to that problem.

- Provide opportunities for regular, low-stakes formative assessment: Graded practice questions, peer instruction sessions, or even informal quizzing allow students to evaluate their understanding of key concepts and to “debug” their learning strategies before a high-stakes exam.

- Encourage learner collaboration: In a social learning environment such as peer instruction, team-based learning, or a laboratory session, learners can compare and contrast their own learning with that of their peers and gain insight into their own personal strengths and growth areas.

One final, impactful way that medical and biomedical educators can encourage metacognition in our learners is by serving as a model of a metacognitively aware, curious, lifelong learner ourselves. For example, you can provide a “peek behind the curtain” and reveal the concepts or practices that you struggled with when learning. Discuss with learners your schedule for planning, monitoring, and evaluating your own performance in the clinic, classroom, or other environment. Ultimately, by improving learners’ metacognitive skills, we can ensure that they will become competent, reflective practitioners who can identify their own weaknesses, create plans to address them, and monitor and evaluate their progress toward their goals.

About the Author

Aidan Ruth, Ph.D. is an assistant professor in the Center for Anatomical Science and

Education at the Saint Louis University School of Medicine. Aidan's areas of professional

interest include humanism in anatomy education, pre-professional anatomy outreach,

and metacognitive training. Aidan can be found on Twitter or contacted via email.

Aidan Ruth, Ph.D. is an assistant professor in the Center for Anatomical Science and

Education at the Saint Louis University School of Medicine. Aidan's areas of professional

interest include humanism in anatomy education, pre-professional anatomy outreach,

and metacognitive training. Aidan can be found on Twitter or contacted via email.